BERKELEY SQUARE: The first time-travel film

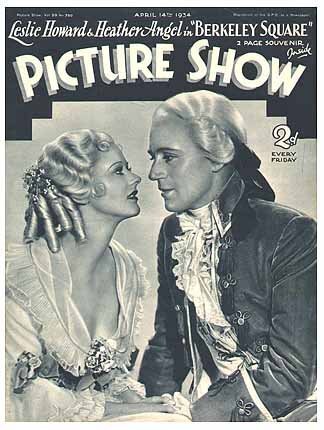

Space travel has been a part of cinema since the early days of Méliès and Walter Booth, but it took a number of decades for the first time travel flick – BERKELEY SQUARE. In 1933, director Frank Lloyd brought the tale of Peter Standish to the silver screen for Fox Film Corporation, a precursor of 20th Century Fox.

Leslie Howard stars as a young American bachelor who inherits a property in England from a distant relative. Once he takes up residence, he becomes obsessed with the diary of a man who shares his name and tries to follow it to the minute in hopes that he will be transported back to 1784. For years BERKELEY SQUARE was considered a lost film, as the picture was such a box office disappointment that no one had bothered to keep a copy. In fact, other than being the first example of a time travel film, its only legacy seems to be as the source material for the 1951 film THE HOUSE IN THE SQUARE.

However, the film was rediscovered in the 70s and remastered. It was also shown at the HP Lovecraft Film Festival in Portland in 2011 (Lovecraft was apparently a fan of the film). I managed to track down the film (never give me a hopeless internet search - I can find anything!) My hopes weren't high because I'm not a huge fan of movies from the 30s unless they feature singing or Alfred Hitchcock. BERKELEY SQUARE is interesting from a SciFi standpoint mostly due to the tremendous lack of actual science in the film.

Unlike in the remake, where an atomic scientist at least toys with science and continues to build inventions once he ends up in the past, Frank Lloyd’s Standish is able to return to the time of lamplighters and cobblestones merely by walking through the rain quickly after reading a diary. Once he ends up there, on the day his ancestor was to meet his fiancé, the film plays like a comedy of manners. His British relatives and friends marvel at the colonial’s tremendous lack of proper etiquette as well as his strange eccentricities, like wanting to bathe every day! Standish makes it worse for himself by continuously mentioning things that haven't happened yet, and people begin to think he is demonically possessed.

A man out of time, he finds his counterpart in Helen, sister of the young woman he was destined to marry. As much as Standish’s mind has been focused on the past, Helen longs to see the future. And in another bit of complete non-science, Helen is able to see the future with all its urban development and war simply by looking through his eyes (“devils! demons!”) After he explains to her that he comes from that other world, Helen begs him to go, knowing he would never be happy here in the past.

Upon his return to 1933, he finds his fiancé confused at his behavior over the last few days. It seems his ancestor had switched places with him. Now, longing for a woman who has been dead for over a hundred and forty years, he knows he cannot marry. The film ends with the hopelessly naive, saccharine epitaph spoken by (the unseen soul of?) Helen, that even though they could not find a way to be together in either of their times, he and she would “be together in God's time.”

After I wiped the barf from my lips, I tracked back to the most interesting dialogue in the film. About 22 minutes into the film, still in 1933, Standish has a conversation with his friend (who you may recognize as Peter Bailey from IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE). Standish suggests that time is like a river, and he may be looking at something to his left as he passes the bank but he doesn't know what's around the corner. Meanwhile, to the person flying a plane up above, it all exists simultaneously: the person in the boat's past, present, and future. He tells his friend that just as he is living now in his time, Peter Standish of 1784 is living in his time - it's just a matter of perspective. If you could just see time from above like a man in a plane, you would see that both Standishes (Standishi?) are still alive in their own time track. “Time is nothing but an idea in the mind of God.”

The scene ends by posing the time-travel paradox for the first time in cinema. Armed with his relative's diary, he confesses he will have to do everything just exactly as his ancestor did, or else he would be in danger of changing time and history. Fortunately for audiences of 1933, the clock chimes and saves them from their mind exploding at the first utterance of that classic trope that had not become classic yet. Standish is off to catch his ancestor, arriving at his house at the same exact time the man with the same name had arrived 149 years earlier. Of course, once he does get to the past, try as he might, Standish is unable to execute the life of his predecessor with enough finesse to fool much of anyone. No sooner does he lay eyes on Kate, the woman the diary says he must marry, then he falls for her sister. After he's made a mess of this timeline and even tells Helen the truth about his arrival (as if that is ever a smart thing to do in a time travel film – I guess he hadn’t seen any yet), he at least has the good sense to bail on 1784, knowing that he can do nothing but screw it all up, especially if he were to marry Helen. All's well that ends well.

Except that's not actually what happens. After a “kiss that has never happened before in history” (or so he tells Helen), he spends the next day ranting and raving at all his ancestors and dropping hints of the Civil War and tanks. He fears he is stuck in this “filthy little pigsty of a world,” and therefore doesn't seem to care much about ruining the future. When he makes it back to 1933 (simply by walking out the door), he doesn't appear to have changed anything significantly. However, a trip to St Martin's Cathedral reveals that Helen died a mere 3 years after he left her in the past. Did his trip to 1784 cause her to die of a broken heart? Interestingly, because the diary never mentioned Helen, only Kate, the audience never knows if Standish changed his own present or not. Maybe Helen was always fated to die in 3 years or maybe he has created a new multiverse as he split the timeline from the diary’s details.

Of course, this is 1933 so Hollywood wasn't ready for that discussion, but I’d like to think the debates that followed PRIMER and LOOPER had their precursor in the audiences of BERKELEY SQUARE. A member of the Production Code Administration (despite requesting a number of “Oh God” and “God knows” removed from the print) wrote “If this picture proves a box office flop, it will be a definite loss to the industry.” While he was probably speaking of the general wholesomeness of pining away in chaste misery, I personally would like to believe he was pondering tesseracts or the grandfather paradox.